Type annotation

You’ll note the use of type annotations throughout the demo sketches. This is a lightweight way to suggest types to your editor, so it in turn can help you explore code and catch errors before your code even runs. It’s especially helpful for catching mistakes that would otherwise be difficult to figure out.

Type annotations live in Javascript comment blocks. Here are some examples:

Declare that the variable el is either a HTMLElement or undefined

/** @type HTMLElement|undefined */let el = document.body;Declare that someFunc takes a string as its single argument, and returns a number

/** * @param {string} value * @returns {number} */function someFunc(value) { // ...omitted...}Or define the structure of an object:

/** * @typedef {{ * name: string * yearOfBirth: number * isBrave?: boolean * }} Cat */

// And later to use it:

/** @type Cat */const bombadil = { name: `Tom Bombadil`, yearOfBirth: 2025, isBrave: true }Type annotations allow you to gain some of the advantages of TypeScript (the contemporary best practice), without introducing additional build steps and complexity. The price paid is some clutter in the source code.

Annotating a function

Section titled “Annotating a function”The most common use of annotations in this code base is to hint what types are expected for function parameters.

Let’s say we have a function that adds some randomness to a number:

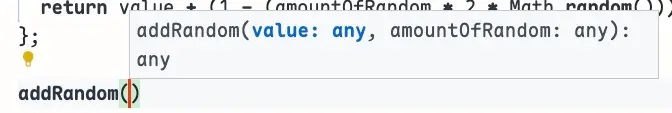

const addRandom = (value, amountOfRandom) => { const range = value * amountOfRandom; return value + (range - (range * Math.random() * 2));};Look at the hovering hint when we start trying to call this function:

We know both arguments should be numbers for the function to work. But we haven’t been explicit about it. And in this case, VS Code can’t possibly deduce for itself what type the parameters are, so that’s why they both show up typed as ‘any’, which means any possible type.

Because of this, it’s easy to call the function with the wrong arguments, leading to unpredictable outcomes or return values.

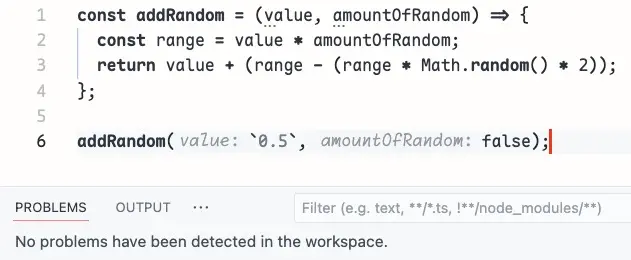

// Oops, we passed in a string and boolean!addRandom(`hello`, false); // Returns 'helloNaN', not what we expect!Not only does this return a bogus result (‘helloNaN’), VS Code is happily reporting there’s no problems in our code. This can cause real issues if we use the result of a function, expecting it to be a number.

As shown above, nothing in the Problems panel, and no red squigglies.

Now, we might not be so silly as to pass in a string, but the following could easily happen.

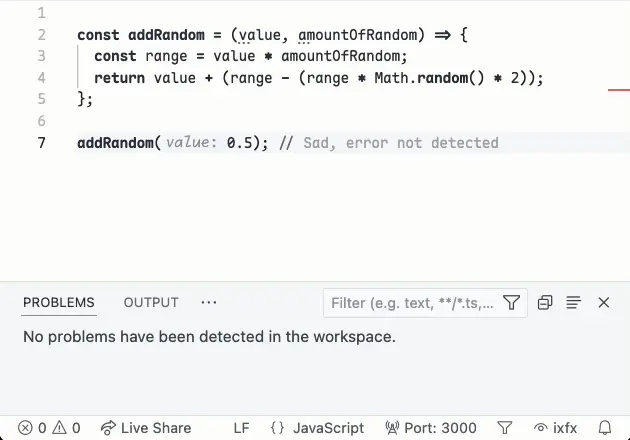

element.style.opacity = addRandom(0.5); // NaNIn this case, we pass in a number for the first parameter but forget to include the second.

No matter what input value is, the function will always return NaN (Not a Number) if the second parameter is omitted.

Again, this will cause other issues of unexpected behaviour if we naively work with the return result of the function. The error can often invisibly propagate through the code, making it hard to figure out why/where it was NaN to begin with.

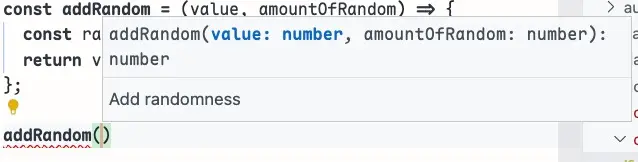

But if we add just two type hints for the parameters, VS Code can immediately tell us about the mistake:

Or if we start typing or hover the cursor over the function, we get info on it:

Type hints thus are super useful for exploring the code and preventing mistakes which can be really hard to track down.

Adding an annotation

Section titled “Adding an annotation”To add an annotation in VS Code, position your cursor in the line above the declaration, start typing /** and hit TAB. It fills out a template annotation:

/** * @param {*} value * @param {*} amountOfRandom * @returns */const addRandom = (value, amountOfRandom) => {Then you can just put in the correct types where there’s the placeholder ’*’. Use the TAB key to jump between the parameters:

/** * Add randomness to value * @param {number} value * @param {number} amountOfRandom * @returns */const addRandom = (value, amountOfRandom) => {The most common types you’ll add are: string, number, boolean and object. Arrays can be hinted using square brackets. For example, an array of strings is ‘string[]’.

Usually the return type is accurately inferred. But if you want to make sure you’re doing what you think you’re doing, add that after the @returns, for example: @returns {number}.

Discovering types

Section titled “Discovering types”If you need to reference a type that is not one of those basic ones, you might need to define your own (see later in this page), or carefully read VS Code’s hover hints to pick up on what its name is.

For example, let’s say we have a function that takes a HTML element as a parameter, and the text to set as the second parameter.

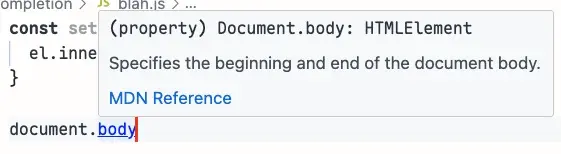

const setText = (el, text) => { el.innerText = text;}We know that ‘text’ can be typed as ‘string’, but what about ‘el’? We could maybe figure it out by looking at things we know are HTML elements, or return them:

Reading those hover hints, we might guess ‘HTMLElement’ or ‘Element’.

Making sense of type errors

Section titled “Making sense of type errors”The following works fine and we get no warnings when we test it passing ‘document.body’

/** * @param {HTMLElement} el * @param {string} text */const setText = (el, text) => { el.innerText = text;}setText(document.body, 'hello'); // No errors as document.body is HTMLElementNow let’s test it with some bad input:

setText('hello'); // Error: Expected 2 arguments, but got 1This error is pretty easy to decode - we’re supposed to pass two things but we’ve only passed one.

And now the next case:

setText(document.body, 0); // Error: Argument of type 'number' is not assignable to parameter of type 'string'This above error is telling us that we must pass in a string for the second parameter, but we’re passing a number. Hopefully it’s pretty clear. These errors can be a bit mysterious however when you’re using variable names. The key thing is to trace back - why is this variable the wrong type? And then you’ll find the problem.

Null checking

Section titled “Null checking”Here’s a valid use case for our setText() function that is giving a warning:

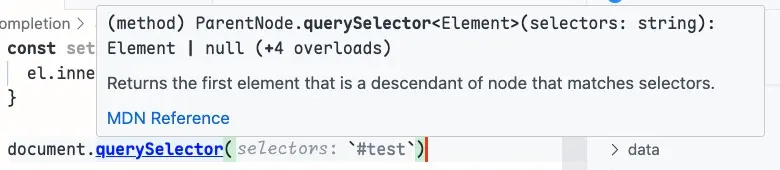

setText(document.querySelector(`#thing`), `hello`);// Error: Argument of type 'Element | null' is not assignable to parameter of type 'HTMLElement'// Type 'null' is not assignable to type 'HTMLElement'."To figure this out, we can hover over ‘querySelector’, and see that it returns ‘Element | null’, meaning it returns type Element or null (for example if there are no matching elements).

VS Code is forcing us to write safer code that doesn’t explode in unexpected ways by handling the possibility of the null value. One way to do so:

// Get the element, and only call 'setText' if it existsconst thingEl = document.querySelector(`#thing`);if (thingEl) setText(thingEl, 'hello');Type assertions

Section titled “Type assertions”But hang on, this still gives an error:

Argument of type 'Element' is not assignable to parameter of type 'HTMLElement'. Type 'Element' is missing the following properties from type 'HTMLElement': accessKey, accessKeyLabel, autocapitalize, dir, and 126 more.What it is telling us now is that we’re trying to pass in an Element which doesn’t have all the things that are expected of HTMLElement. querySelector might return something which is a valid Element, but not necessarily a valid HTMLElement, such as SVG.

You might be confident enough that is in fact of type HTMLElement, but still want to verify it’s not null - just in case you made a typo in the selector or HTML, for example. One approach would be to wrap the querySelector() call in a type assertion. Note the use of the type hint and ( ) around the querySelector call.

// Assert the result of the function to be HTMLElement or nullconst thingEl = /** @type HTMLElement|null */(document.querySelector(`#thing`));if (thingEl) setText(thingEl, 'hello');Now the errors are gone because we’re asserting that it’s the narrower HTMLElement type and we explicitly handle the case if it’s null.

If we were super confident, we could skip the null check, by asserting it is a HTMLElement.

const thingEl = /** @type HTMLElement */(document.querySelector(`#thing`));setText(thingEl, 'hello');We’re basically telling VS Code to trust us, which makes the warnings go away. If, in fact, ‘thingEl’ gets to be null, your code will still break when it runs. So you should generally be cautious about solving warnings with type assertions, because the underlying risk might still be there but now it’s invisible to you.

Another way to solve this particular issue would be to make the parameter type for setText to be more permissive and do the safety-checking in the function. An exercise for the reader!

Defining a type

Section titled “Defining a type”An example of a type is:

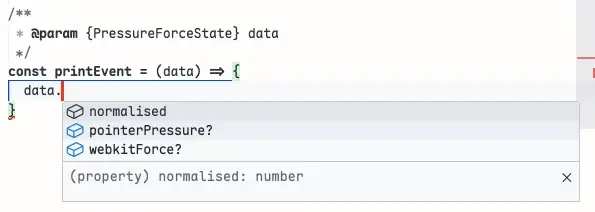

/** * @typedef {{ * webkitForce?: number * normalised: number * pointerPressure?: number * }} PressureForceState */Note the ’?’ at the end of some names. This means the property is optional.

If we have the above type, these objects all match the type PressureForceState

{ webkitForce: 0.53, normalised: 0.59, pointerPressure: 0.843 }{ normalised: 0.59, pointerPressure: 0.843 }{ normalised: 0.59 }But if a required property is missing or the wrong type, it won’t match:

{ normalised: false } // normalised is supposed to be a number, not boolean{ webkitForce: 0.5, pointerPressure: 0.98 } // Missing 'normalised'Objects can always have additional properties, and still match a type:

{ normalised: 0.59, colour: 'red' }If we had a function that took this type as input, we could use it like so:

/** * @param {PressureForceState} data */const printEvent = (data) => { // do something, eg with data.normalised}Or we can define a variable to be of that type:

/** @type PressureForceState */const f = { normalised: 1};Applying the type for functions and variables is how you get the benefits of them. One nice thing is that when you type the variable name and hit ’.’, you get a list of its properties. No need to type which one you want, and avoids the risk of typos.

Disabling

Section titled “Disabling”To disable all this magic, add these lines to the top of your source:

/* eslint-disable */// @ts-nocheckYou could also edit your project settings and ensure that "js/ts.implicitProjectConfig.checkJs": false.

Importing types

Section titled “Importing types”VS Code is smart enough to find and use type definitions from imported libraries, such as ixfx, even when it’s not explicit.

In the example below, envelope is correctly typed to the interface Envelopes.Adsr :

import { Envelope } from '@ixfx/modulation.js';const envelope = Envelope.adsr();It may be necessary to manually import types when you are referring to them in a type annotation.

In the below example, we import the type Point:

/** * @typedef {{ * position: { import('@ixfx/geometry').Point} * id: string * }} Thing */More Examples

Section titled “More Examples”Unions

Section titled “Unions”Sometimes we might need to show that it can be one of several types, for example: string|number means string or number type.

/** * Returns the number form of `value`, converting from string if necessary * @param {string|number} value * @returns number */const convert = (value) => { if (typeof value === `number`) return value; return Number.parseFloat(value);}

convert(0.5); // 0.5convert(`0.5`)); // 0.5convert(false); // Error, parameter is not a numberIn the above example, our function is only meant to take a string or number as an input, and now it correctly warns us if we pass in something else, like a boolean.

Inline types

Section titled “Inline types”If it seems overkill to name the type, you can define it inline.

In the below example, the makeRelative function takes a point as input and returns a point.

/** * @param {{ x:number, y:number }} point */const makeRelative = (point) => { return { x: point.x / window.innerWidth, y: point.y / window.innerHeight }}

makeRelative({ x: 50, y: 100 }); // Yields an { x, y } objectIn the above example, a @returns typing is not needed because VS Code can infer the return type automatically.

Because the return type is known, if we assign the value to a variable, VS Code knows it is a point:

const r = makeRelative({ x: 50, y: 100 });r.x; // All fine, 'x' is part of the return type of 'makeRelative'r.hello; // Error 'hello' does not exist on { x: number, y: number }In this way, we the benefits of typing the function flow beyond the function itself.